One of the most moving events in American history has been all but lost to our history books — the heroic journey of the Fool Soldiers to rescue a group of women and children during the Minnesota Uprising of 1862.

The Minnesota Uprising, also referred to as the U.S.-Dakota War and the Great Sioux Uprising, took place in August of 1862. Patti A. DeCory summarizes the events in Fool Soldier Band, (PDF form):

Miles to the east in Minnesota the Santee were reaching their breaking point in August, 1862. They had suffered crop failures the previous year and hence nearly starved during the 1861-1862 winter, now their annuity goods and cash were late. As they impatiently waited, they petitioned the traders for credit which was denied and provided one of the most famous quotes of these contentious days; storekeeper Andrew J. Myrick said, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.” He did not live to regret these words.

The Minnesota Uprising of 1862 began innocently enough with some returning hunters, some broken eggs, and a dare. By nightfall on August 17th, five white settlers were dead and the Indians were gathering to access their situation. Although several of the chiefs are said to have been against the uprising, “the young braves could, and did, go counter to their wishes. Once the decision had been made, the chiefs, although reluctant, felt that they had to go along with their people.”

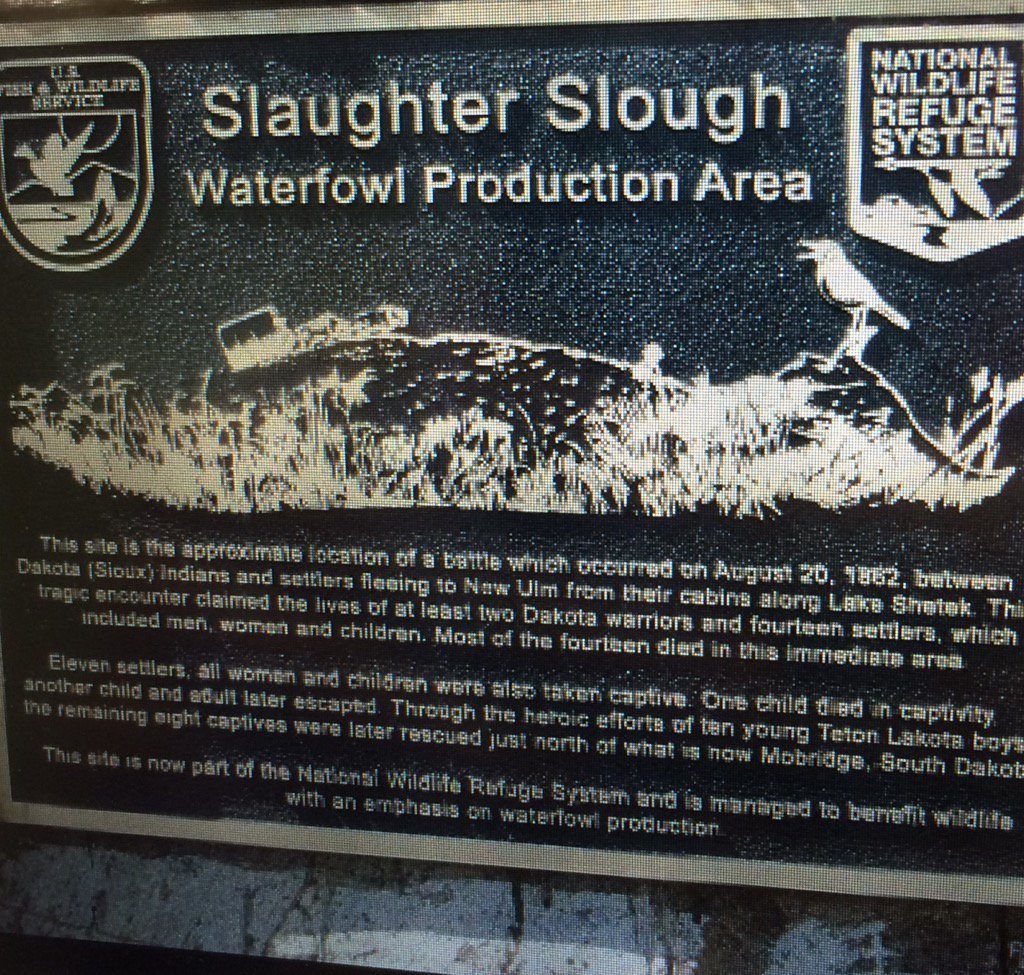

The events culminated in tragedy at a settlement on Lake Shetek:

On August 20th the uprising arrived at Lake Shetek in Murray County in southern Minnesota. The settlers unsuccessfully hid in a swamp, later known as “Slaughter Slough;” after shooting at the moving grass for several hours, the Indians called out the women and children offering them safety. By the next afternoon, Santee Chief White Lodge and his band were headed west with their eight captives: Mrs. Julia Wright, Mrs. Laura Duley, and six children.

In November, word of the captives reached a group of young Teton Lakota men. These men had formed a group based on non-violence and helping all people, leading some others to mockingly call them “Fool Soldiers.”

The Fool Soldiers decided to make the journey to the Santee camp to negotiate a trade and rescue the hostages. Since they believed in non-violence, they gathered and bought supplies like blankets, coffee and sugar to offer in return for the women and children.

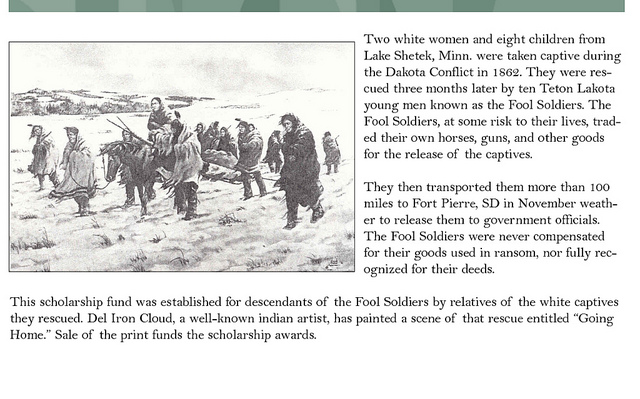

The Fool Soldiers made the dangerous trek to the camp and spent three days negotiating for the release. When they finally succeeded, they were left to journey back with only one horse (the others had been added to the trade) in bitter cold and snow. They had very little clothing and few supplies for either themselves or the rescued captives.

The Fool Soldiers carried the smallest children and put one injured woman on their only horse. One soldier gave his moccasins to the other woman because she was barefoot. They were later able to trade a gun for a cart to put the children in, but it was too heavy for their horse to pull so the Fool Soldiers took turns pulling it themselves.

The journey was dangerous, as they had to be on guard against those who considered them enemies from all sides of the conflict (including U.S. forces who might see them as kidnappers) and they also were battling brutal cold and ice. They succeeded, though, and returned the captives to Fort Randall.

Following the rescue (and a later rescue of starving Lakota on Medicine Creek), they were not greeted as heroes by either side of the conflict. When they arrived at Fort Randall they were imprisoned by the U.S. until the end of the conflict, and it is believed that two of them died while in the stockades. Once released, they were ridiculed and shunned by many in their tribe and their log homes were whitewashed. They eventually relocated to other areas (life was difficult for some of the rescued women and children after the rescue, as well).

The story is told in the DVD “Return to Shetek: The Courage of the Fool Soldiers,” through the voices of both the rescued captives and the young men who risked their lives to bring them home. It’s difficult to find the video now (our family has a copy that we purchased locally at Lake Shetek State Park, since we live near the site of the conflict). It can be ordered in Minnesota through interlibrary loan and may be available through libraries in other states, as well. Be aware that parts in the beginning may be difficult for young or sensitive children.

Barbara Britain has written up an excellent five page discussion guide to go along with the DVD. The guide asks questions such as “Why do you think a child is narrating the story?”, “Why were White Lodge’s people not welcomed in South Dakota?” and “What were and still are the four basic rules of the Fool Soldier Society? (Respect, compassion, responsibility and accountability)”. (Unfortunately, I am no longer able to find this study guide online. Please comment if you know a place to find it again.)

There are several Southern Minnesota sites you can visit with kids to accompany your studies of the Fool Soldiers. One is obviously Lake Shetek State Park, the original site of the settlers and captives and the site of one of the original cabins. A memorial also stands there for the men, women and children who did not survive the attack. There is a monument at “Slaughter Slough,” which you can learn more about here.

Families can also visit Fool Soldier Band Monument in Mobridge, South Dakota and the Minnesota Historic Society has quite a few books to learn more about the U.S.-Dakota of 1862.

Harry Charger, a descendant of one of the original Fool Soldiers, talked about his family’s history at the dedication of the Currie monument. He talked to the crowd and said some Native Americans are still bitter that the Fool Soldiers helped the settlers.

Minnesota Public Radio reports his words:

“We’re still being ridiculed to this day. We’re being called traitors. We’re being looked down upon a lot of times,” said Charger. “But we stand tall. Because like I said, if you have compassion in here, their ain’t no force in this entire universe that will beat you.”

A scholarship fund now exists for descendants of the Fool Soldiers to attend college. The fund was created by the ancestors of both the Fool Soldiers and the families they helped rescue.

And what eventually became of the Fool Soldiers? Those who survived continued their work. A.B. Welch wrote in The Welch Dakota Papers in 1924:

Lewis and Clark, in 1804, mention that they heard of a band of Sioux warriors, whose solemn oath was that they would never turn back from any danger or give way to their enemies…

In 1864, the band of Fool Soldiers among the Tetons had but thirteen, or less, members and a new member could not be elected until there was a vacancy, and was much sought after. Some of the members of the famous soldiers society have been as follows:Waaneta (Charger) – a grandson of Capt. Lewis (not the Waaneta of the Sissetons). This man died in 1900. His wife died at Devils Lake, January 1916.

Kills and Comes, Swift Bird, Four Bears, Mad Bear, Pretty Bear, Sitting Bear, One Rib, Strikes Fire, Red Dog and Charging Dog.

These men all achieved fame early in life. The descendants of these famous men of brave and spectacular deeds, are living today on the Standing Rock.

Famed Dakota artist Oscar Howe’s paternal grandfather, Don’t Know (D. K.) Howe, was also member of the Fool Soldiers rescue party.